The Noose that Dangled

By Malavika Parthasarathy

I watched him smile. It was a gentle smile. His skin was dark, burnt almost. And woven into its burnished brilliance were creases that chased one another, weaving a tapestry of pain. “My childhood,” he said, “was filled with games of galli-danda and marbles”. His hands and legs shook as his brown eyes possessed a peculiar numbness - a numbness that was somehow rimmed with understanding and they looked into mine, and he said that he wouldn’t be able to walk to the gallows. He spoke of a noose that dangled menacingly and a noose that dangled beckoningly.

The stories may have been different because the voices are different - in the subtle inflections, in the differences in pitch, harmonizing to create music that sings primarily of pain and poverty, but which also sings of the unabashed whimsy of a system that claims to be fool-proof, which proclaims its ability to bring justice to both the victim and the perpetrator, but which does neither.

One of the reasons I was doing this was for myself. I was doing this to better understand the terms that are so frequently used in popular discourse - caste oppression, gender inequality, intolerance, and economic oppression. Terms that have now become so much more than mere words and phrases.

An instance that comes to mind is a visit to a village in Karnataka. While I was always aware of caste shaping our lives and our daily interactions insidiously, I had never truly understood just how much power it could wield. In Karnataka, in a nondescript village that was a two-hour drive from Bangalore, caste was not merely manifested in ‘naavu’ and ‘avaru’(us and them) as was in the rest of the state, but in a tangible, taut tension – a heaving river that threatened to spill over and devour in its tempestuous wake the invisible constraints that bound the residents of the village to their fragile peace. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that these experiences have provided me with a better understanding of the issues that plague our nation and the system. But I could say that my experiences have provided me with a better understanding of my own ignorance.

This project has helped me forge bonds with people I would never have otherwise closely interacted with, providing me with an array of people I could filch food from. The project taught me to brave bathrooms with malfunctioning flushes, led to a significant improvement in my Hindi, and taught me that waiting list 54 is probably not the best risk one should take. It has also made me more aware of my position of privilege, including the fact that I could easily return to the world of air-conditioning and plush chairs, and that it is only a quirk of fate that has led to this stark difference between me and those on the other side.

In that rickety bus, I sat thinking about why I was a part of this. Was it because I was learning about the criminal justice system, being made more aware of the flaws that are deeply entrenched in it? Was it because I was learning to survive in inhospitable climes, or was it because I knew that this was an opportunity to experience something I, in all likelihood, may not be able to avail of again?

The wind slipped in through the gap between my shawl and my skin. I shut my eyes and I could see Him again. Him with the dark skin and saffron turban.

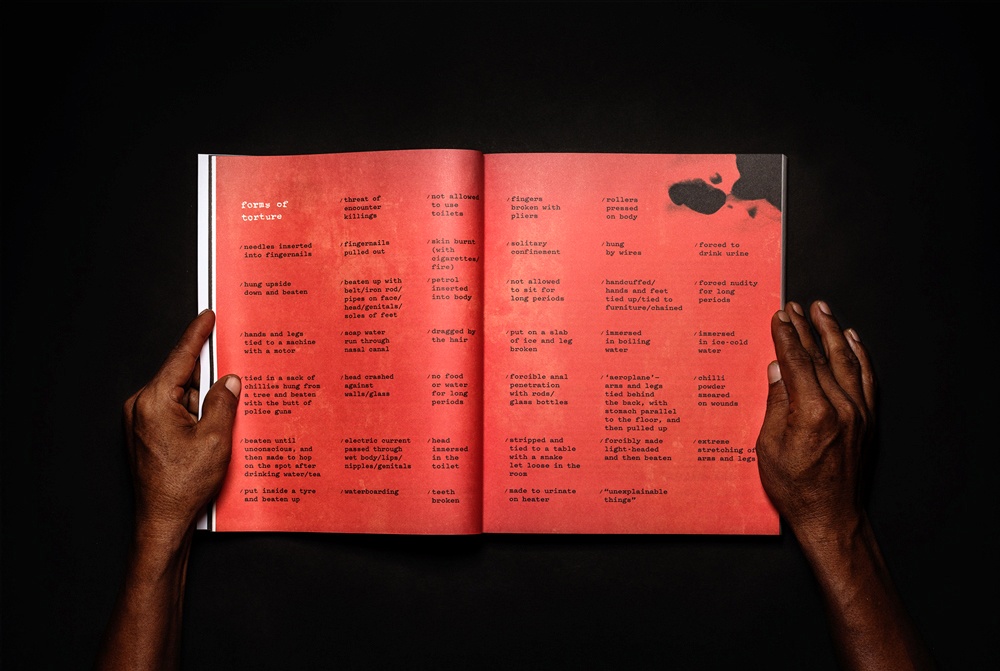

For a minute, I was him, and I could see, in a hazy, confused, blur, the khaki-clad policeman, swooping in in the dead of the night, the thana where they hurt me in unmentionable places, where I pressed my inky thumb against sheet after sheet of blank paper, the court where the ‘judge-saab’ muttered unintelligibly in a language I didn’t understand, the faces of my family etched into my brain as I waited for them to visit (they never did but I couldn’t blame them), the bewildering procedures and the trials and the grimness of the courtroom, the nice lawyer who promised that I would be out in no time but who would, every month, with a wry, thin-lipped smile, ask me for a couple of thousand rupees; I even thought of the newspaper clippings that I had saved. They thought I was a monster, eyes flashing with bloodlust, with calloused hands and long, dexterous fingers. I thought of the grey confines of the jail, where the only solace I derived was from chanting hymns dedicated to a God I wasn’t sure I believed in.

And I pictured his knock-kneed limbs collapsing beneath his frail, hunched body as he walked to the gallows. I saw a rope, hewn with dry hemp, nibbling into the nape of his neck, and then gnawing with the famished fury of a society that longed for blood. And glistening against the colorlessness I could see the gimlets of his blood and the blood of the woman he said he hadn’t raped – both leaving the same slightly metallic aftertaste.

Again, I could see the noose dangling menacingly and the noose dangling beckoningly. And I suddenly knew who I was doing this for.