MATTERS OF JUDGMENT

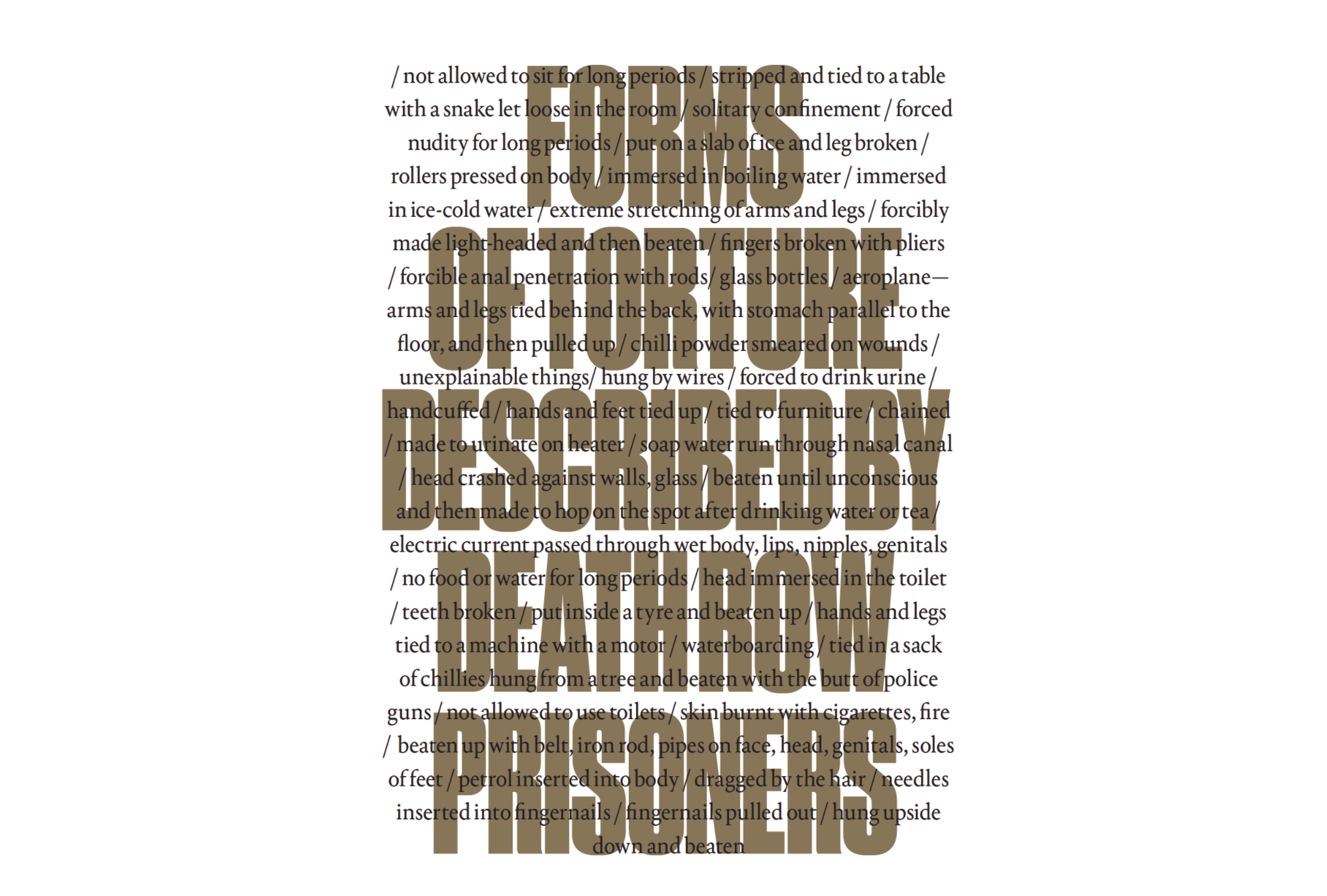

Matters of Judgment is an opinion study on the criminal justice system and the death penalty with 60 former judges of the Supreme Court of India. The 60 former judges adjudicated 208 death penalty cases between them at different points during the period 1975-2016. The study was an attempt to understand judicial thought and adjudicatory processes that govern the administration of the death penalty within India’s criminal justice system. We received academic support from Professor Carolyn Hoyle (Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford), Dr. Mai Sato (University of Reading) and Mr. Saul Lehrfreund (Death Penalty Project, London) in conducting this study.

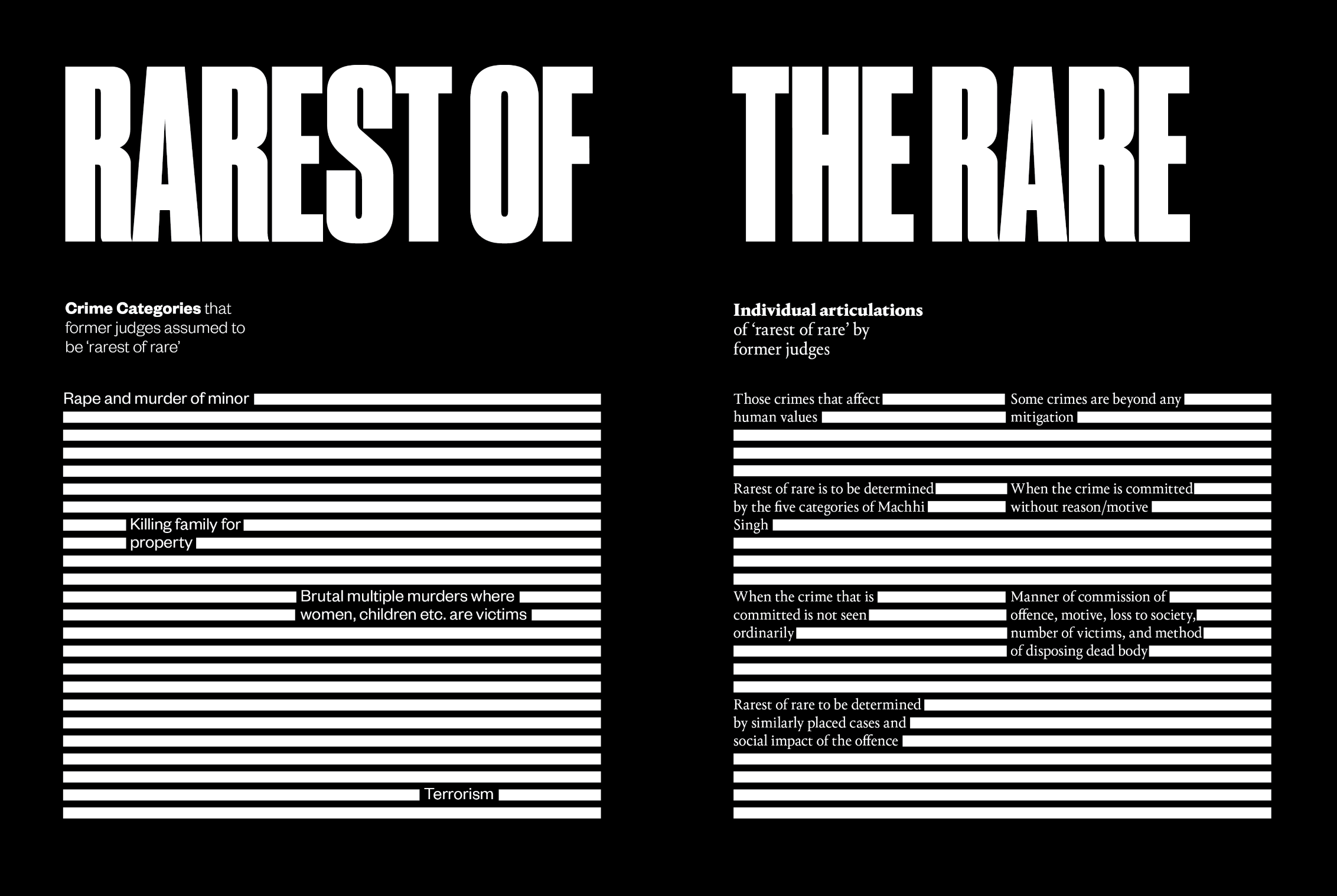

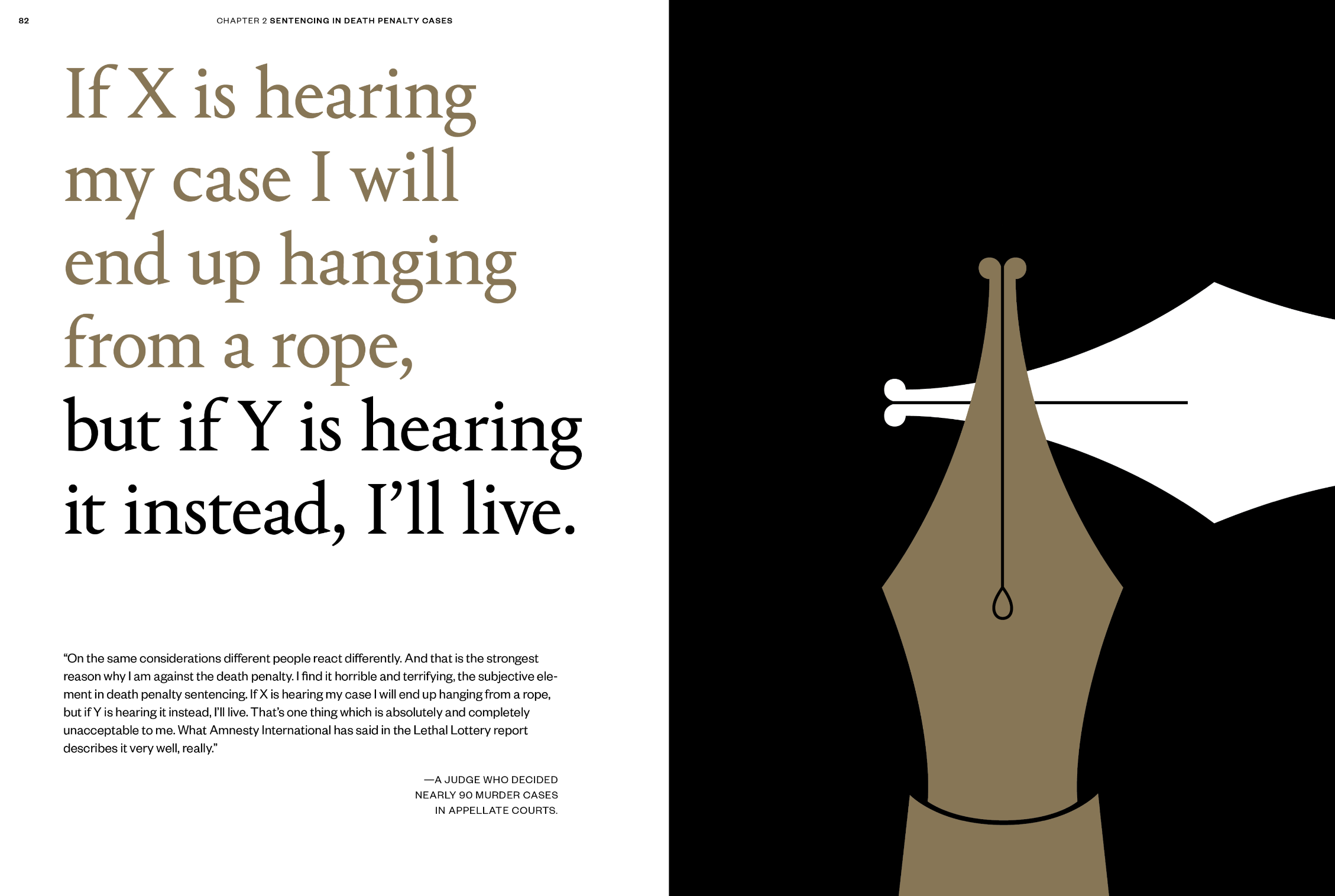

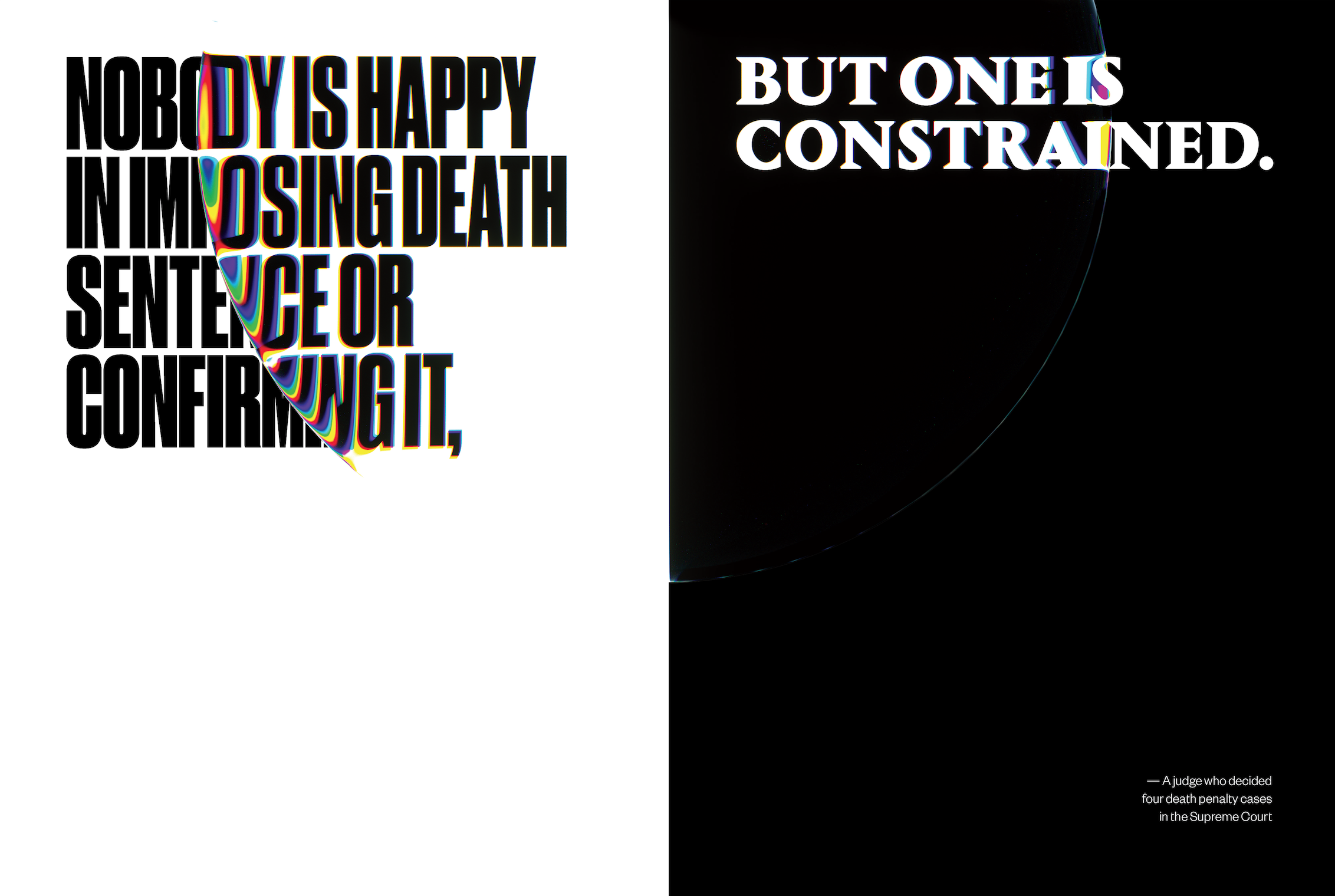

We carried out in-depth, semi structured interviews with former judges with a questionnaire that guided the interviewers. The questionnaire was broadly divided into three themes which included, investigation and trial processes, sentencing in death penalty cases, and judicial attitudes towards the death penalty. Besides the questionnaire, three hypothetical cases were also used as a tool during interviews. Each hypothetical case consisted of relevant evidence on record for a capital offence committed, and a few sentencing factors. The former judges were asked to decide these cases by determining guilt, and sentencing the accused.

Most interviews lasted between 90 to 120 minutes, and were conducted by two interviewers, at either residential, or office spaces of the judges. Given the nature of interviews, and the varying time availability across judges, we were unable to obtain responses to every question from all the interviews, which is evident in the varying number of responses on different issues.